By Andrew Melillo

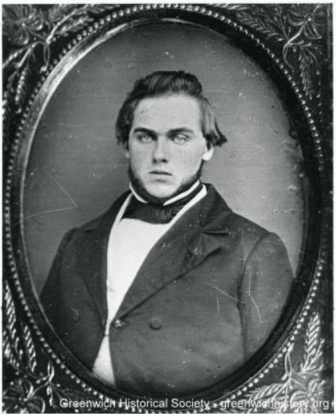

Photograph courtesy of Greenwich Historical Society

A few days ago on September 19, marked the anniversary of the passing of Daniel Merritt Mead, a native son of this town and one whose memory and legacy should be remembered from time to time by the town’s citizenry.

Daniel dutifully served his county in a time of chaos and confusion. He was in the Yale Class of 1854, and he passed the bar and practiced law in New York and Connecticut in 1855 and 1856.

He was a founding charter member and the first Junior Warden of the masonic lodge Acacia 85 and first formal historian of the town.

Daniel Knapp writes the following of Daniel Merritt Mead in his book, Muskets and Mansions:

“Captain Daniel Merritt Mead, a twenty-eight year old lawyer who had already written a comprehensive history of Greenwich, commanded I Company. Mead was born in Cos Cob on June 2, 1834. After attending Yale and Law School, he was admitted to the Connecticut Bar and began practicing law in Horseneck. He married Louisa S. Mead, completed his history of Greenwich in 1857, and enlisted as Captain of I Company, the Tenth Regiment, Connecticut Volunteers, on September 6, 1861.

The Tenth was mustered into service at Camp Buckingham near Hartford, Connecticut. From there, the regiment, Mead‘s I Company included, entrained for Annapolis, Maryland, where it was assigned to the First Brigade of ‘Burnside’s Division.’ With two months of training and drill to form and firm it, the regiment shipped out on transport for its first engagements in North Carolina.

The Troops remained on board for more than five weeks. Provisions were barely adequate. Sickness quickly seized the confirmed men and for the most part, life aboard the transport was miserable. Finally, on February 7, 1862, they landed on Roanoke Island, where, to the astonishment of the regular army officers on hand, the Tenth Regiment ‘fought like veterans.’

From that point on, the Tenth fought in practically all the nameless battles, fights and skirmishes that took place in eastern North Carolina and along the James River in Virginia for the remainder of the war. The battle record reads like a provincial Piedmont train schedule: Slocum’s Creek, Plymouth, Trenton, Tarboro, Rawle’s Mills, Hamilton, Williamstown, Goldsboro….

Then came Kinston, in December, 1862. Seven thousand rebels held this North Carolina hamlet. Several Union regiments had attempted to carry the enemy position – without success. Now the Tenth was called in from the rear. It passed one beaten brigade, then three regiments of another. The order was given to charge. Rolling onward, the Tenth literally had to leap over the men of three more Union regiments lying down in the line of battle.

Ahead stood a rebel brigade holding the bridge over the Neuse River and the road into the town. The Tenth routed these defenders almost peremptorily. The bridge was aflame now, set ablaze by the retreating Confederates. The Tenth raced across as the timbers crackled and the bridge began to yield beneath their weight.

Sweeping by four field pieces that had been pounding at them as they advanced, the Tenth stormed the town itself. When it was over, the regiment had captured five hundred prisoners, eleven artillery pieces, hundreds of small arms, and uncounted valuable documents. They had suffered one hundred and six killed and wounded in action.

Then came Whitehall, Goldsboro again, Sealbrook Island, James Island, then Fort Wagner. They were withdrawn for a brief rest in St. Augustine, Florida – sixty percent of the regiment incapacitated by sickness and disease.

Brief was the word for it. Soon they were back on their maddening milk run of battles. By April, 1864, the tracks cut through the once-placid country and around the James River in Virginia…Walthall Junction, Drewry’s Bluff, Deep Bottom – just nine miles from Richmond, Strawberry Plains, Springfield, Deep Gully, Fuzzell’s Mills, Petersburg, Chapin’s Farm, Fort Harrison, New Market Heights.

At one point, the entire Army Corps, of which the Tenth was a component, was suddenly exposed to a surprise attack on the North Bank of the James River. Only the Tenth Regiment saw the rebels coming. Unaided, they mobilized and turned back a Confederate force that outnumbered them ten to one.

By September of 1864, the regiment’s three-year term of enlistment was up. From this point onward, substitute recruiting filled its ranks. Only ninety of the Tenth’s original members remained until the close of the war.

One Brigade Commander had said of them, ‘…for steady and soldierly behavior under most trying circumstances….they may have been equaled – but never surpassed.’ The tribute had been paid for dearly. Some few lucky ones had returned home to Greenwich in that weary September. They majority had been cut down by cannon shards, musket balls, exhaustion and disease.

Daniel Merritt Mead had been one of those who fell. Promoted to Major for valiant service, he had contract typhoid fever in the summer of 1862. Sent home, he died in Greenwich before the leaves had turned color that same year. Daniel Merritt Mead had been, at twenty-eight, a lawyer, historian and proven leader of men under fire. What accomplishments he might have reached – for his town, his state and his country – had he survived the War of Secession.”

And so, I ask the citizens of Greenwich, from time to time, to remember Daniel Merritt Mead’s honor. To remember his sacrifice, to remember his name.

I have always remembered Mr.Mead from the time I first received a copy of "Muskets To Mansions" for Christmas 1966.

ReplyDeleteMy 2nd great grandfather "Elisha Miles" served in the the 10th Co.I.