By

the mid-nineteenth century steam powered ships emerged as a new innovation in

travel for goods and people. Sometimes accidents happened, often with tragic

consequences. I’ve read about such things in the newspapers of the times. A

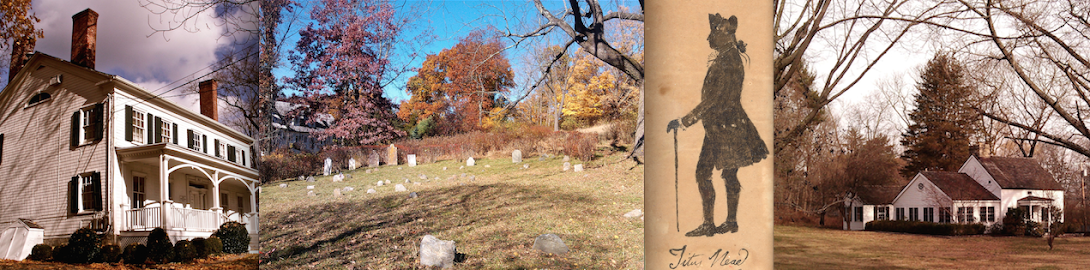

gravestone in Greenwich’s New Burial Grounds Association Cemetery references

one such sad ending.

Jared

Mead was the son of Daniel Smith Mead (1778-1831) and Rachel Mead (1779-1859.

He was born in Greenwich, Connecticut on July 25, 1816.

He

married his wife Clarinda on May 28, 1843. They had five children; only two

would outlive Jared:

Watson N:1844-1863

Susan E: 1845

David Newton: 1846

Adelia Rachel: 1848-1848

Emma Huldah: 1852-1934

In 1852 Jared Mead was the

captain of a schooner owned by Augustus Stedwell of Brooklyn, New York. Mead

was 36 years old at the time. His gravestone states:

Jared Mead,

who perished on the

Hudson River in the sinking of

his Schooner the

JONATHAN BORAM by the steamer

Francis R. Skiddy.

Died October 14, 1852,

aged 36 years & 3

months.

Husband thou art gone to

rest

Thy toils and cares are

o'er

And sorrow pain and

suffering now

Shall ne'er distress

thee more.

While

in the Hawaii State Library near downtown Honolulu I found this story of the

first page of the New York Daily Times, dated Saturday, October 16, 1852:

Collision

on the Hudson River-Supposed Loss of Life

Verplanck’s

Point, Friday, Oct. 15

A

schooner, supposed to be the Jonathan Booream, belonging to AUGUSTUS

STEDWELL, of Brooklyn, Captain JARED MEADE, was run into and sunk last evening

by the steamer Francis Skiddy, when opposite this place. The schooner was

broken in two, and the stern floated ashore with the compass and a box

containing the schooner’s papers, with the captain’s coat and hat. The fate of

those on board is not known, but they are supposed to have been all drowned.

Insights

into history sometimes appear in the most unexpected places and circumstances.

On the same day I was at the Hawaii State Library I ran across this article in,

of all places, The Pacific Commercial Advertiser, published weekly in Honolulu

by Henry M. Whitney (today known as the Star Advertiser). The following

appeared on the first page of the July 1, 1865 edition. It focuses on the fate

of the Frances Skiddy in Spring, 1865:

Letter

from New York

(634

BROADWAY,) New York,

March

28th, 1865.

MR.

EDITOR: - A few days since I left Troy in the beautiful steamboat Frances

Skiddy. I chose this boat in preference to the cars, because of the greater

comfort and finer view of the Hudson River scenery, to say nothing of the

satisfaction of knowing that I was in no danger of one of those railroad

“smash-ups” which have become so fearfully common within the last month or two.

The

boat was heavily laden with merchandise and the spacious saloons full of

passengers. When about ten miles below Albany we heard a sudden crash of

timbers accompanied by a heavy jar. The boat began to tip and soon the decks

stood at an angle of forty-five degrees to the horizon. Men shouted, women

shrieked and fainted, and children cried, while the steam-whistle screamed

shrill and clear above them all. For a few minutes the scene of wild confusion

and dismay was indescribable. Just at this crisis something about the engine

gave way and a volley of steam rushed into the main saloon filling it in a few

seconds. Strange to say no one was badly burnt.

We

had struck a rock, tearing a large hole in the bottom of our craft. She was

rapidly sinking, slowly righting as she sank. In less than ten minutes the

dining-saloon was full of water. Tables, chairs, dishes, and burning lamps were

floating about. There was great danger that the lamps would set the boat afire,

but no one dared venture in to get them.

In

five minutes more the water was a foot deep on the next deck. The

baggage-master was not to be found, so we broke into the baggage room with

axes, got out our carpet-bags and retreated to the upper decks, where we were

rejoiced to see that a steam-tug. Which was going down the river with a number

of canal boats, had just come to our rescue.

By

the time we had handed the ladies, children and personal baggage over to these,

the Skiddy had sunk seven or eight feet more and grounded. After waiting there

a half an hour, the Hendrick Hudson, on her way from Albany to New York, picked

us up. We were happy to have escaped without the loss of a single life, and

concluded that it was not unreasonable to expect entire freedom from accidents

either by land or water. The dangers encountered in trusting your life in your

little inter-island coasters, (to say nothing of the Kilauea,) are perhaps no

greater than the perils of travel in this most civilized and christian land.

(signed

“Viator”)